Over the summer break a member of the CEFA team visited New Zealand. After touring around the Auckland Museum a question came to mind: why didn’t New Zealand join with the six other British colonies at Federation and become an Australian State?

New Zealand is mentioned in the covering clauses of the Australian Constitution when defining the States:

The States shall mean such of the colonies of New South Wales, New Zealand, Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia, and South Australia, including the northern territory of South Australia, as for the time being are parts of the Commonwealth, and such colonies or territories as may be admitted into or established by the Commonwealth as States; and each of such parts of the Commonwealth shall be called a State.

First British Contact

And it just so happened that on the flight back from New Zealand there was a documentary series available to watch about Joseph Banks and the voyage of the Endeavour around New Zealand and then the East Coast of Australia.

This documentary suggested that while both the Aborigines and the Māori were not happy to see the ship and the explorers, the encounters of Joseph Banks and the ship’s crew with the Māori in New Zealand were different to the encounters with Australian Aborigines. The Māori have been in New Zealand for 800 years while Aborigines have been in Australia for at least 50,000 years. Even after encounters with the native peoples, Captain Cook planted the English flag in New Zealand and Australia.

Convicts

The first fleet landed in Sydney in 1788 with 751 convicts on-board. Governor Arthur Phillip claimed about half of Australia, New Zealand and Norfolk Island and named it New South Wales. Over time, different parts of New South Wales were broken off into separate colonies starting with Tasmania. And in 1829 Western Australia was also claimed (although it was called Swan River for a few years).

Penal colonies were set up all around the country, which were not like the prisons that we have today. Soldiers and convicts had to work side-by-side and relied upon each other. Many convicts that had much needed skills or trades were able to set up businesses (bakers, carpenters etc) and were running these businesses while they were still under sentence.

Folklore tells us that the prisoners sent to Australia had been convicted of crimes such as stealing loaves of bread. But there was also political prisoners sent here. This included political reformers from Scotland and England, Chartists, mutineers including a notable surgeon, welsh rebels, Irish nationalists, artists, poets and writers. There were even former UK politicians that had been convicted of crimes such as embezzlement sent to Australia.

Once a sentence had been completed former convicts were free to set up a life in Australia. Some were even given land to start farming. In many way, there were many more opportunities for former convicts in Australia. But as you can imagine with all these people mixing together and social hierarchy not being as important as back in England, a new type of society was being formed.

The British didn’t set up New Zealand as a penal colony (SA wasn’t either). They didn’t do much with New Zealand for some time. Meanwhile European sealer and whalers began to arrive there and some convicts also headed to New Zealand after being released. There are also reports that escaped convicts who mutinied during voyages to and from other Australian penal colonies sailed to New Zealand and started new lives.

The missionaries that began moving to New Zealand in the early 19th century were claiming that the country was becoming rather lawless by the 1830’s. The whalers, sailors and sealers were running amok. The British Parliament were asked to do something about this.

While Captain Cook had planted the English flag at Mercury Bay New Zealand in 1769 and Captain Arthur Phillip had claimed New Zealand as part of New South Wales in 1788, the UK Government had not yet been represented there.

The Treaty of Waitangi

The UK Parliament sent James Bushby to New Zealand as its official British Resident and he arrived in 1833. The Declaration of Independence was drawn up by Busby, without British authorisation, and signed by 52 Māori chiefs in 1835.

Captain William Hobson was then appointed by the UK Parliament to obtain sovereignty over New Zealand. He, along with Busby negotiated the Treaty of Waitangi with the Māori chiefs to re-establish British control of New Zealand. About 40 chiefs signed it on the first day, 6 February 1840, and by the end of the year nearly all chiefs had signed it.

The Treaty established a British Governor of New Zealand, recognised Māori ownership of their lands, forests and other properties, and gave the Māori the rights of British subjects. In return the Māori people ceded New Zealand to Queen Victoria, giving her government the sole right to purchase land.

After this period, many settlers began to arrive from the United Kingdom. Some stopped in Australia for a few years or a few months and then moved to New Zealand. Because most settlers were free people, rather than former convicts, those settling in New Zealand tended to think of themselves as quite different to Australians. The distance from Australia also help to reinforce these types of thoughts.

The experience of the Māori was very different to the Aborigines in Australia. The Māori were allocated seats within the New Zealand Parliament in the 19th Century:

Four Māori seats were established by the 1867 New Zealand Parliament to give Māori a direct say in Parliament.

It was around this time that people within the colonies were starting to discuss federating. Representatives from New Zealand attended some of the first conventions in Sydney in 1891. However, New Zealand representatives did not attend the drafting weekend aboard the paddle-steamer SS Lucinda (but neither did WA).

New Zealanders just weren’t that keen on joining the federation (and neither were WA). As time progressed and the drafting of the Constitution was completed New Zealanders had to make up their mind.

A Royal Commission

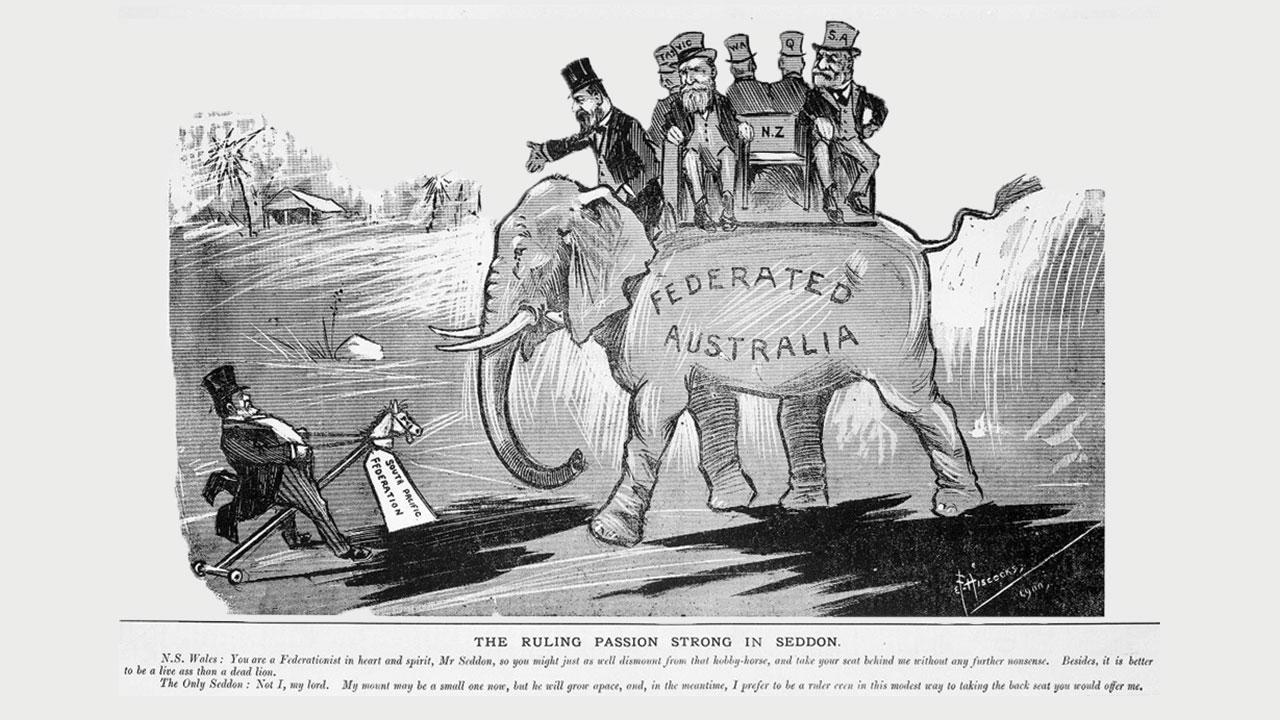

The New Zealand Premier Richard Seddon set up the royal commission in 1900 to buy time and gain an understanding of public opinion about becoming a State of Australia. Richard Seddon himself was not a fan of New Zealand becoming an Australian State. The Royal Commission reported back that:

The stretch of some twelve hundred miles of sea ... is a weighty argument against New Zealand joining the Commonwealth

But that wasn’t the only argument. New Zealanders just weren’t interested in uniting with Australia. The NZ Ministry of Culture and Heritage write:

The prevailing view was that New Zealanders were of superior stock to their counterparts across the Tasman.

In Australia, one of the reasons that had been put forward to federate was the need for a united defence force. New Zealanders thought that the British would protect them if needed:

So long as Britannia ruled the wave, New Zealanders could rely on imperial protection of their own coastline. In the event of Great Britain losing command of the sea, Australia and New Zealand could not rely upon being able to render material assistance to each other.

They also felt as though they were competitors or rivals of the Australia colonies rather than partners. But the Australian colonies also saw themselves as competitors of each other. And New Zealanders also saw no need for a High Court when the Privy Court was available to them.

In any case, the ten man Royal Commission in New Zealand recommended not becoming a State of Australia. But the option was left open for them to join at a later date. Hence why we find New Zealand named in our Constitution where the States are defined.

New Zealand Constitution

New Zealand doesn’t have just one document that forms their Constitution. There are several Acts of Parliament, the Treaty of Waitangi, letters patent, conventions and court decisions along with other bits and pieces that comprise their constitutional arrangements.

The disadvantage of an uncodified systems means that it is easier for the Government to make changes to the constitutional arrangements. However, New Zealand does give their citizens the opportunity to force citizens initiated referendums. The result of the referendum is not binding, but gives the Government an understanding of the electorate’s opinion.

Unicameral Parliament

The New Zealand Legislative Council was an appointed body that was abolished in 1950. There was no referendum. In order to abolish the Upper House New Zealand first had to adopt the Westminster Act (something Australia was reluctant to do too). Then in 1947 the Parliaments of both the UK and New Zealand passed Acts to amend the New Zealand Constitution Act. It was a few years later that the Prime Minister of New Zealand appointed a ‘suicide squad’ of 20 members to the legislative council to vote to abolish the upper house (similarly to Queensland in 1922).

Voting

The New Zealand voting system is Mixed Member Proportional (MMP):

It is a proportional system, which means that the proportion of votes a party gets will largely reflect the number of seats it has in parliament…. Its defining characteristics are a mix of MPs from single-member electorates and those elected from a party list, and a Parliament in which a party's share of the seats roughly mirrors its share of the overall nationwide party vote.

A proportional voting system is more important in countries with unicameral parliaments as the separation of powers is weaker.

The future

Do you think it is likely that New Zealand will become the seventh Australian State in the future? Or have our cultures moved apart even further in the decades since federation?