The Australian Parliament holds an original copy of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. This piece of British legislation enabled the Australian Constitution to take effect on 1 January 1901. There were two original copies of it held in London until 1988, when one was loaned to Australia for the bicentenary celebrations. We never gave it back.

An Australian document?

From at least 1849 there was a movement towards uniting the Australian colonies. Federationists formed into campaign groups to spread the message. Politicians began to discuss federation. A Constitution would have to be written.

At a conference in 1890 it was decided that a Constitutional Convention would be held. Each colony, including New Zealand, appointed delegates to attend the 1891 Sydney Convention where the first draft of our Constitution was written. Shortly afterwards there was a financial crash and community support waned. The federationists continued to campaign and at the 1893 Corowa Conference it was decided that another Constitutional Convention should be held. Victorian John Quick moved a motion at the Conference and stated:

That in the opinion of this Conference the legislature of each Australasian colony should pass an act providing for the election of representatives to attend a statutory convention or congress to consider and adopt a bill to establish a federal constitution for Australia, and upon the adoption of such bill or measure it be submitted by some process of referendum to the verdict of each colony.

The motion was carried unanimously. 10 delegates were elected from five colonies and they met for three sessions at the 1897-98 Constitutional Conventions (Queensland and New Zealand declined). They worked tirelessly. The ideas and reasons behind every single word in the Constitution was discussed as they were being written. There was a lot at stake.

There were huge debates, even arguments. But in the end there was compromise. The delegates voted on the accepted wording of each section of the Constitution. After an initial failed referendum in NSW in 1898 the Constitution was again altered. Another vote was held in 1899 in each colony except WA and the people endorsed the Constitution.

We were British colonies

Our new Constitution had to go through the British Parliament. As such, later in 1899 the Parliaments of the five colonies each passed an Address to Queen Victoria asking/praying for Federation. By this time there was a lot going on in the background. Chief Justices of the colonies, Lieutenant-Governors and Governors who were not completely happy with the final draft were writing to the British Government urging them to alter the Constitution.

At the request of the British Government delegates from the Australian colonies were sent to England to assist and explain the document. La Nauze writes:

Late in January 1900 a conference of premiers agreed that each colony should appoint a delegate, but that each delegate should represent all the federating colonies. They were to be instructed to press for the passage of the Bill without amendment.

Alfred Deakin from Victoria, Edmund Barton from NSW, Charles Kingston from SA, James Dickson from QLD and Philip Fysh from Tasmania sailed to London to act as the representatives of the colonies while the Constitution Bill was being debated in the British Parliament.

The British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain wanted amendments. Deakin saw himself, Barton and Kingston as staunch federationists, but was worried that Dickson and Fysh might be persuaded by Joseph Chamberlain’s arguments. They fought for months over three changes:

The delegates, apart from Dickson, took their stand on the simple proposition that the Draft Bill should be passed into law without the alteration of a single comma….Their precious Bill, endorsed by the people of the Australian colonies, should not be touched.

Deakin warned Chamberlain that alterations may delay Federation by causing a third referendum. Apparently Chamberlain had not considered this. He concentrated his efforts on one change that he thought was essential. Appeals to the Privy Council on constitutional matters. Not everyone in the Colonial office agreed. John Anderson, also from the Colonial Office wrote:

The Australians hold that the Constitution is of their own framing and is for themselves to interpret except where outside public interests are concerned. They feel most strongly, and whether they are right or wrong, I do not see that we should be warranted with interfering.

In the end there was a compromise made on appeals to the Privy Council. The Australian delegates in London sent drafts back and forth to people in Australia. In the end the final draft of the alteration was written by the Chief Justice of Queensland, Samuel Griffith. Section 74 of the Constitution would permit appeals to the Privy Council on constitutional matters as long as the High Court agreed. So even the final alteration requested by the British Parliament was written by an Australian. With a few slight technical adjustments the Bill passed through the British Parliament and was given Queen Victoria’s assent on 9 July 1900.

WA held a referendum shortly afterwards, which was agreed to by the people and they joined the Federation before the Constitution took effect on 1 July 1901.

So what happened to the Act?

There were two copies of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 produced on vellum in London. One was held as the official record of Parliamentary proceedings in the Record Office of the House of Lords (now called the Parliamentary Archives). The other was held in the Public Record Office (now the National Archives).

Not long after Federation, members of the Australian Parliament started to request certain original documents held in British institutions relating to Australia, to be sent to Australia. This included the Endeavour and Resolution logs. Senator Josiah Symon (who was previously for a short period the Attorney-General) called these documents our ‘title deeds’ and moved a motion in the Senate in 1909 to officially request them. The Senate passed the resolution and the Governor-General sent it to the Colonial Office in London.

The Colonial Office was not forthcoming. They replied that they had no authority to send these documents to Australia and offered to produce facsimile copies. The Australians did not want copies and the British Treasury vetoed it anyway.

In the meantime Public Libraries in Australia began purchasing private journals and documents that related to Australia’s colonial history. A statue of Flinders was erected in Sydney in 1922 in a deal that saw the Mitchell Library purchase Flinders’ journals and other materials. A year later Kenneth Binns from the National Library urged Prime Minister Bruce to purchase a journal of Cook’s that was available in the private market.

Throughout the following decades further requests were made to the British institutions and Government to obtain records that were important to Australia. They were denied and copies were offered. In 1948 the British Public Records Office began copying materials requested by the Australians. By 1993 over 10,000 reels of documentation had been copied.

Getting the Constitution

In 1984 Australian Attorney-General Evans and Prime Minister Hawke began a campaign to obtain one of the two original copies of the Constitution. The House of Lords Record Office and the Public Records Office both refused when they were asked. British Prime Minister Thatcher, while sympathetic, rejected the proposal when she was asked by Bob Hawke on four separate occasions. Our Prime Minister did not give up. The battle continued for four years.

In a conciliatory move, the Public Record Office loaned us their copy of the original Constitution to be displayed in Parliament House for the bicentenary celebrations in 1988. This was probably made a mistake. More than two million Australians went to see it while it was on display and 1989 rolled around and we were in no rush to give it back. Bob Hawke had clearly stated throughout his negotiations with the British Government that he wanted to retain an original copy of the Constitution in Australia. Some people in the British Parliament were not happy that we still had hold of it. In February 1990, Bob Hawke wrote an article addressed to the British people in The Times. His article titled ‘Please complete our birth certificate’, explained why the document was so important to Australia.

The British Government finally relented. On 3 May 1990 the British Solicitor-General stated in the Parliament that:

It would be right to find a way to offer the document to the Commonwealth of Australia as a gift….the Prime Minister has now written to Mr. Hawke offering a gift of the document, and that offer has been warmly accepted.

Finally, our nation’s most important document, written by Australians and voted for by Australians, was ours to keep. The British Parliament passed a law to release our Constitution from their archives. They also had to pass legislation to replace the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act within their archives.

The Original Australian Constitution is now held in Canberra at the National Archives who have it on loan from Parliament House. You can also see our facsimile copy (courtesy of Parliament House) at the Australian Constitution Centre at the High Court.

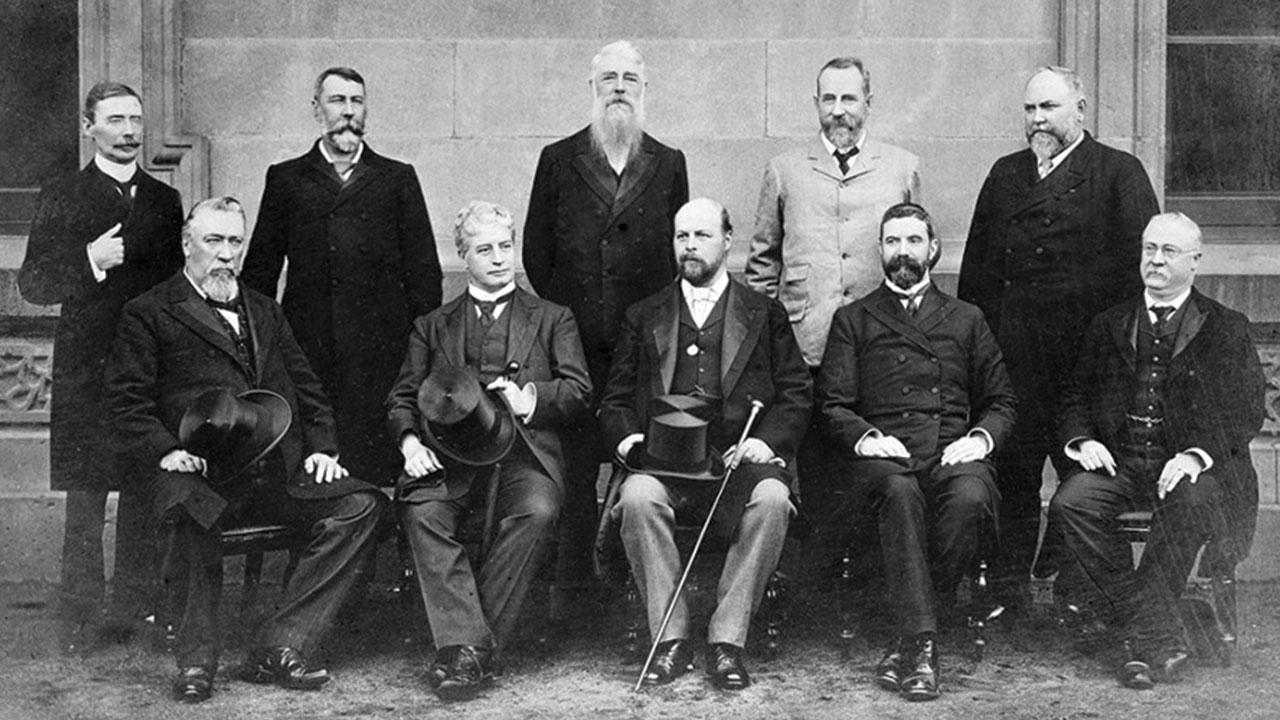

Image Source: NAA A1200, L13365

The Ministry of the Barton Government. From Left to Right (standing): Senator James George Drake, Senator Richard Edward O'Connor, the Hon Sir Philip Oakley Fysh, the Hon Charles Cameron Kingston, the Hon Sir John Forrest. Seated: the Hon Sir William John Lyne, the Rt Hon Edmund Barton, Governor-General Lord Tennyson, the Hon Alfred Deakin, the Hon Sir George Turner